Ever since the Sankhala family began its lodges with the intent to synergise forest conservation efforts with eco-tourism, it has involved locals in the day-to-day workings of the lodge. Many of the staff members have been around for decades (in some cases, the second and third generations are also finding viable career options here), getting trained to cater to the guests. The lodge works with local artists and collaborates with village women for decoration of the lodge’s walls.

Bandhavgarh Jungle Lodge is by and large plastic-free. For the record, the breakfast inside the park is sent in neat paper bags and traditional Indian-styled tiffin carriers. “Our focus is on reuse and upcycling and in minimising waste,” says Sadhvi. The staff is encouraged to generate ideas on creating more sustainable measures for the lodge.

From woven lampshades to wastebaskets in bamboo, Bandhavgarh Jungle Lodge is an ode to the local crafts that exist in abundance. To empower the local population, products are sourced directly from the locals while ensuring that they are in sync with the local crafts.

Additionally, Bandhavgarh Jungle Lodge is plastic-free.

It’s 50 years since Kailash Sankhala took the helm at India’s Project Tiger - and his family wildlife lodge is still doing a roaring trade, finds Tamara Hinson. MTEN minutes into a stroll along Bandhavgarh National Park’s boundary when I start questioning my keenness to see the wildlife. My companion is naturalist Simranjit, whose stories amuse and terrify in equal parts. He chuckles when he realises I mistook the flimsy fence for some kind of barrier.

Alarm calls from monkeys grew increasingly shrill, the shrieks of peacocks ever louder. The jungle was on red alert. Such animal warnings about predators are just what you want to hear if you’re searching for a big cat in India: in this drum roll of agitation, our 4x4 rounded a corner and came to an abrupt halt. In front of us, a tiger had stepped out of the undergrowth.

Poner Singh is a stubborn man. When India’s National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) invited him to swap his hand-to-mouth existence in the teak forests of the Satpura Tiger Reserve for a free house and five acres of farmland on the outside, the father of two declined.

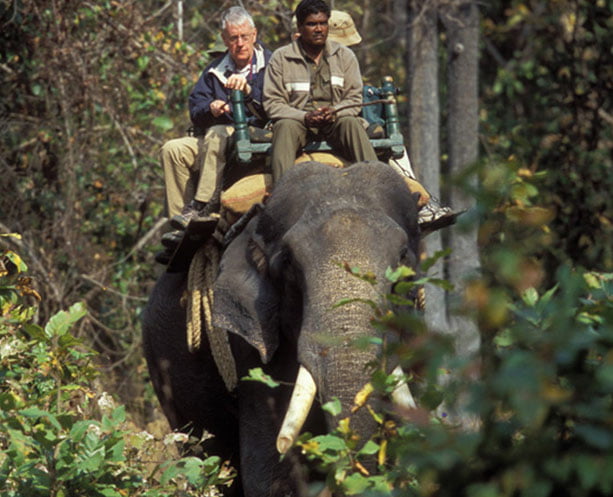

Sankhala is certain I’ll see a tiger. He tells me this as we bump along the dirt roads of Bandhavgarh National Park, India’s tiger country – 1,540km2 of swaying grassland and tropical forest where the mighty Bengal tiger roams freely.

Tamara Hinson heads to Bandhavgarh National Park, one of India’s best conservation success stories, in search of big cats.

From the moment I enter Bandhavgarh National Park, it’s clear the wildlife is never far away.